“Pump up the water from under glaciers, and the weight of the ice will cause it to rise most of the way up a well. Then, you pump it the rest of the way and pipe it to stable ice nearby.”

– A geoengineering idea from The Ministry for the Future by Kim Stanley Robinson.

Geoengineering, at its core, involves manipulating Earth’s systems on a large scale to reduce the effects of climate change. These interventions target the ocean, land, and atmosphere, aiming to mitigate global warming’s impacts. But can such large-scale technological solutions truly solve a global problem like climate change?

Renowned ethicist Stephen Gardiner offers three compelling reasons why geoengineering may not be the silver bullet some envision:

1. Unequal Distribution of Benefits and Harms

Geoengineering’s outcomes are unlikely to benefit everyone equally. The effects of these technologies will vary across regions, creating winners and losers.

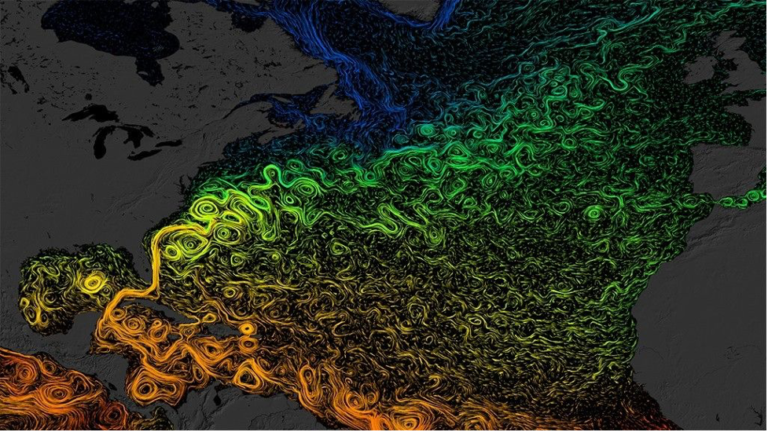

For instance, ocean fertilization—adding nutrients like iron to surface waters to stimulate phytoplankton growth and sequester carbon dioxide—has demonstrated unintended ecological consequences. This artificial nutrient boost can disrupt marine food webs, altering species compositions from microscopic plankton to large predators like whales.

Unlike a universally beneficial lighthouse that aids all nearby sailors, geoengineering risks exacerbating existing inequalities. Some regions may experience improved conditions, while others suffer severe weather changes, biodiversity loss, or food insecurity.

2. Governance and Decision-Making Challenges

Global implementation of geoengineering requires consensus, which is incredibly difficult to achieve. Powerful nations or corporations could dominate decision-making, prioritizing their interests over those of vulnerable communities or less-developed countries.

For example, developed nations may push geoengineering initiatives that suit their climate goals, while neglecting the needs of countries in the Global South. This raises critical questions about fairness and justice—how do we ensure that all stakeholders have an equal say in decisions affecting the entire planet?

The lack of an inclusive governance framework makes it nearly impossible to regulate geoengineering equitably on a global scale.

3. Unintended Consequences and Uncertainties

Geoengineering operates on the principle of altering natural systems, but Earth’s systems are highly interconnected. Intervening in one part often leads to unforeseen impacts elsewhere.

For instance, large-scale solar radiation management, which involves reflecting sunlight away from the Earth, could unintentionally alter precipitation patterns, disrupt monsoons, or create droughts in critical agricultural regions.

Moreover, our understanding of these systems remains incomplete. This uncertainty amplifies the risk that geoengineering’s unintended consequences could outweigh its intended benefits, creating more harm than good.

Is Geoengineering Compatible with Climate Goals?

While proponents argue that geoengineering can complement climate mitigation efforts, it contradicts the principles of the Paris Agreement, which emphasizes equity, transparency, and precaution.

Take direct air capture as an example. This technology captures CO2 from the air and stores it underground. While it promises to offset emissions, it has significant drawbacks (Peter Coy, 2023):

- Hidden Agendas: Many oil companies advocate for direct air capture because it could lead to enhanced oil recovery. CO2 stored underground often pushes more oil to the surface, perpetuating fossil fuel extraction.

- Energy Intensity: Direct air capture requires enormous amounts of renewable energy, which could be better allocated to cleaner solutions like solar or wind power.

- The Carbon Cycle: The process of capturing and storing CO2 ironically produces additional emissions, creating what could be termed a “carbon dioxide cycle.”

The Bigger Picture

While geoengineering may sound like a futuristic solution, it is not a replacement for immediate and equitable climate action. The focus should remain on reducing emissions, transitioning to renewable energy, and addressing systemic inequalities that exacerbate climate impacts.

Policymakers must think beyond short-term fixes and consider the ethical, social, and environmental consequences of large-scale interventions. Geoengineering should not distract from the urgent need to phase out fossil fuels and support vulnerable communities in adapting to a changing climate.

As Gardiner warns, manipulating Earth’s systems carries irreversible risks. Before taking such a leap, humanity must carefully weigh the costs and benefits, ensuring that no one is left behind in the quest for a sustainable future.

+ There are no comments

Add yours