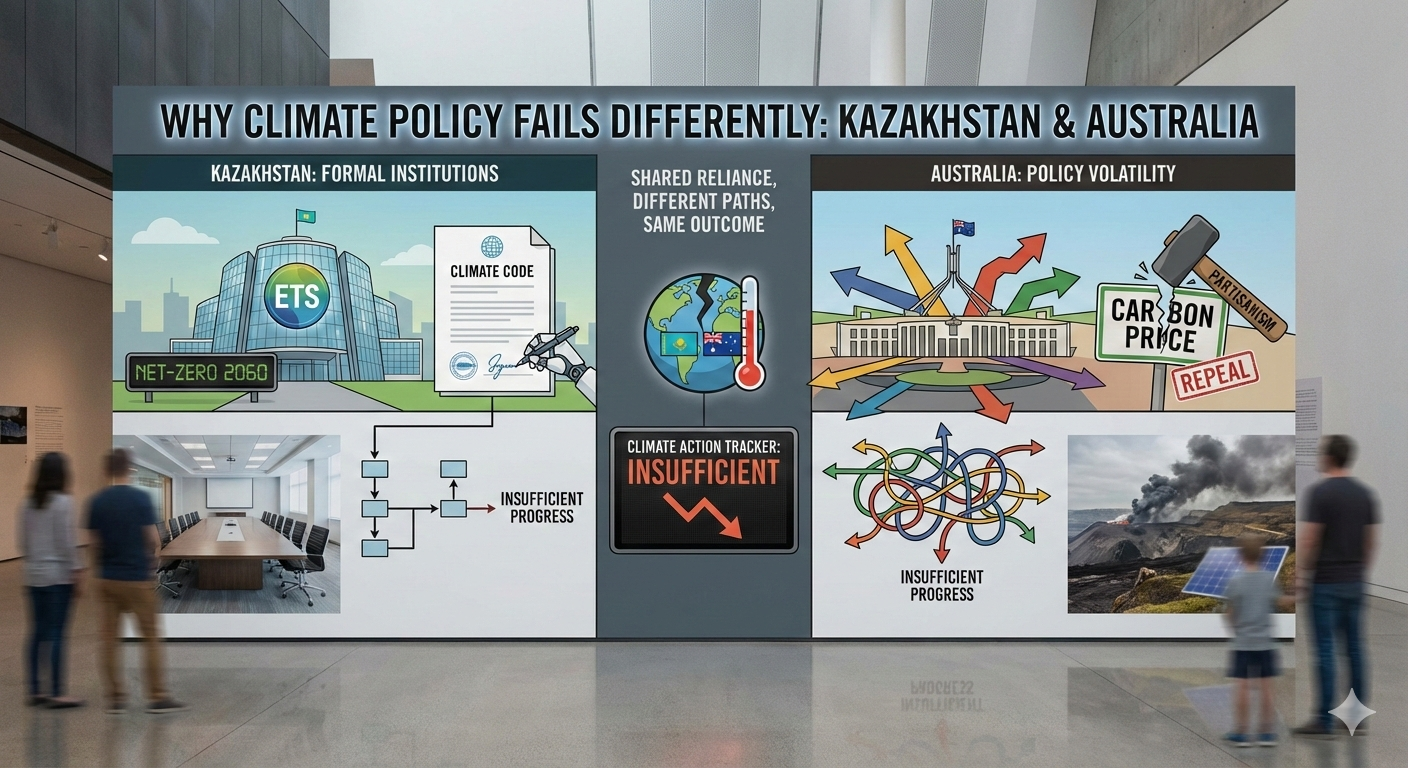

Kazakhstan and Australia are both deeply reliant on fossil fuels. Both are internationally committed to fight climate change. But their climate policies are completely different and still fall short in practice. Kazakhstan has been quick in terms of adopting formal climate institutions. It was the first country that introduced Emissions Trading System (ETS) in Central Asia and legally codified a net-zero target by 2060.

Australia on the other hand has experienced years of climate policy volatility, partisanism and even repeal of carbon prices. One seems decisive; the other chaotic. The outcomes are very similar. Both countries are not on track to meet their emissions target and according to Climate Action Tracker (CAT), their overall progress remain INSUFFICIENT. This difference is not about failure or success but it is about how failure is produced.

Kazakhstan: Ambition on Paper, Inertia on the Ground

Kazakhstan portrays the image of climate ambition which is impressive at the first glance. in 2020, the government announce the ambitious target of carbon neutrality by 2026. This target was later enshrined in law through the Strategy of Achieving Carbon Neutrality by 2060. The Nationally Determined Contribution of the country commits that it will cut greenhouse gas emissions by 15 percent of its level in 1990 by 2030, And if the country receives the international support and funds, it will reduce the emissions by 25 percent.

The core mitigation instrument of Kazakhstan is the Emissions Trading System (ETS), which was initiated in 2013. It is basically modeled on the EU ETS and it applies to large power and industrial installations under a mandatory cap-and-trade framework. Firms get free allowances; have an option of trading surplus permits and they can generate offsets by having approved projects. The plan of having a voluntary carbon market have also strengthened the reputation of Kazakhstan as an early institutional mover in the region.

The ETS is facing some challenges such as low coverage, weak liquidity in the market, and allocation criteria that largely favor incumbent firms. Also, there is low enforcement, low penalties and low compliance. Energy pricing reforms have been delayed severally, and coal subsidies are still in existence. Formal climate institutions will not halt the rise in emissions until the 2030s, as projected.

To a large extent, this gap is explained by the governance structure. Climate policymaking process is very centralized and the power is in the hands of the executive. Institutional accountability has been moved across ministries, disrupting continuity and as well as bureaucratic capacity has been eroded. Long-term strategies and policies shift according to presidential interests, not institutional processes.

Public scrutiny is limited. Civil society engagement is weak, media control is limited and subnational governments are under-resourced and lack power. As a result, climate commitments and the continued expansion of fossil fuels do not receive much opposition domestically. There are further plans and construction of new coal-fired power plants, which completely contradict proclaimed decarbonization pathways. The climate policy in Kazakhstan is full of strategies and declaration but thin enforcement.

Australia: Volatility, Conflict, and Partial Progress

The climate policy of Australia unfolds quite differently. Climate change has emerged as one of the most political hot topics in national elections, dividing parties, voters, and regions. The changes in the direction of policies have been drastic with changes of government.

The biggest intervention occurred during the Gillard Labor government, which instituted a carbon pricing mechanism under the Clean Energy Act of 2011. The policy was adopted in 2012, and its initial price was a fixed carbon price, which was to be replaced by emissions trading. During its operation, covered emissions decreased, and country-level emissions were reduced slightly.

The political backlash was swift and long-term. The opposition packaged carbon pricing as a damage to economy and electorally toxic. The Coalition won government and, in 2014, repealed the scheme, becoming the first state in the world to abolish a scheme already in operation. It was replaced by the Emission Reduction Fund, which is a voluntary, offset-based scheme financed by public expenditure. Emissions soon rebounded.

Throughout the rest of the decade, climate policy was undermined and unstable. The growth of fossil fuels was encouraged, international pressure was resisted, and ambition remained low. This changed once again following the election of the Albanese Labor government in 2022. The new government declared a 43 percent emission decrease by 2030 (compared to 2005 levels) and restated a net-zero goal by 2060

The reformed Safeguard Mechanism is now the major policy instrument, controlling emissions from large industrial facilities in the country. These facilities have declining baselines, and if they exceed them, they are required to buy carbon credits. This framework proposes an aggregate cap on covered emissions and also includes provisions on emissions from new projects.

However, there are still major issues. According to an independent assessment, existing policies are so week to achieve the 2030 goal without enhancement. Excessive dependence on offset credits itself causes concerns over environmental integrity. Renewable energy implementation and the development of the transmission infrastructure are not keeping up with demand. Meanwhile, the approval of new coal and gas plants continues, and the emissions embodied in the exports of fossil fuel far exceed national emissions, but are not in the scope of national climate policy.

Power, Accountability, and the Shape of Failure

The comparison between Kazakhstan and Australia reveals a greater pattern.

In Kazakhstan, power is centralized, which allows quick adoption of policies, but it shields the decision-makers. When it comes to climate commitments, there are minimal domestic political costs of failure to implement. Policies can exist without real enforcement, and contradictions can persist without consequences.

Australia climate policy is one that is likely to be overturned and watered down as a result of democratic competition. Elections, federalism, and multiple veto points are ways through which power is divided and the cost of decisive action in politics is increased. At the same time, these same institutional features generate feedback processes that force governments to respond to social pressure. The outcome is not gridlock versus efficiency, but symbolic compliance versus contested compliance.

Fossil Fuels as the Common Constraint

In both countries, fossil-fuel dependence limits climate ambition but through different channels. Fossil fuels in Kazakhstan form the basis of state revenues and regime stability. The interests of oil, gas, and coal are inbuilt into the state via state-owned enterprises and elite networks. Decarbonization is not only dangerous to economic output but also to the political foundations of power. Any climate policies that directly challenge these interests are quietly diluted during implementation, no matter how strong they appear on paper.

Power in Australia operates in a pluralistic manner through which fossil-fuel interests are mediated. Although the role of coal and gas exports are not fiscally vital to the state, these exports remain economically and politically important. The industry lobbying, campaign financing and media discourses which focus on jobs and competitiveness shape the policy design. The governments are pushed to less confrontational and cheaper instruments, such as offsets, while more ambitious measures are framed as politically risky.

Different systems. Different pathways. The same outcome: the protection of carbon-intensive sectors and resistance to structural transformation.

Ending Where It Matters

When comparing Kazakhstan and Australia, it is possible to see that climate failure does not take the same form everywhere. Climate policy does not break down naturally; it is a product of political systems. Centralized authority can generate grand commitments that are not executed, while democratic fragmentation produces unstable, compromised progress.

To the extent that fossil fuels remain deeply entrenched in domestic political economies, international climate agreements will continue to make more promises than they deliver. The actual divide is not simply authoritarian versus democratic leadership, but whether political systems are willing and able to confront interests for which decarbonization is politically costly.

+ There are no comments

Add yours