Introduction

Billions of dollars are being pumped into the international climate funds annually promising to assist the vulnerable countries to cope with the climate change. However, in some parts of Central Afghanistan, families cover hours on donkeys in search of water to drink as drought becomes more severe. This discrepancy between the financial promises and the realities on the ground is a grave flaw in the global climate policy, since money cannot resolve the issues, to which people are unfaithful. Climate finance without climate literacy is just a piece of paper, documents, report and transfers that cannot change anything long term since they do not reach the human ability to utilize them powerfully. This essay holds that the existing climate diplomacy and finance systems produce a systematic underestimation of climate literacy, which results in a cycle where money is spent, but it is not embodied, initiative is planned, but not realized, and policy is authored, but not acted upon. Not only do such efforts lead to a waste of resources, but inequality between the countries that are able to move complex climate financing systems and those that are not is increasing.

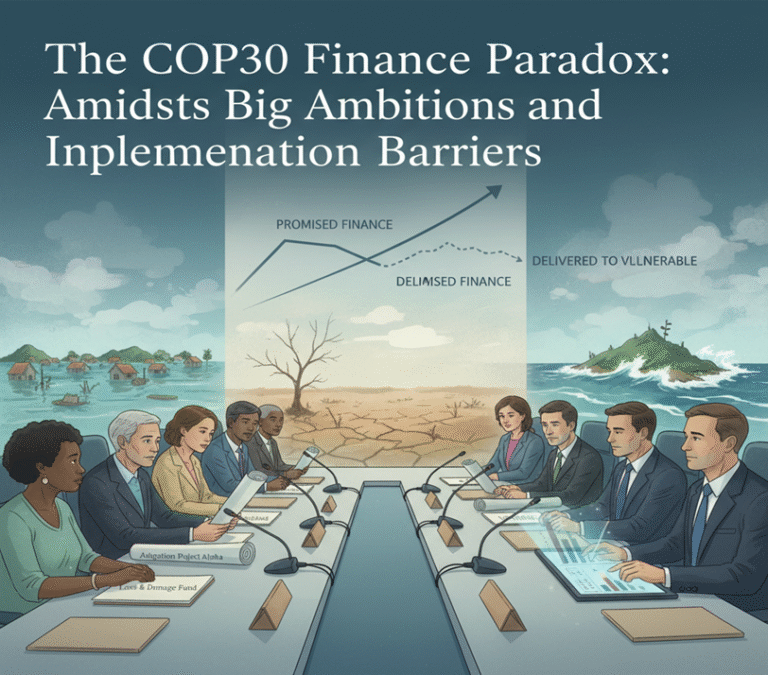

The Climate Finance Paradox

The climate finance has increased drastically but the effect is not significant. Green Climate Fund itself is expected to raise 100 billion dollars a year, yet developing countries and especially least developed countries (LDCs) and small island developing states (SIDS) are still struggling to access it because of a chronic problem of capacity gaps. This is where the paradox comes in: the money is there, and it cannot get into the hands of its most oppressed people.

It is not an issue of processes or documents. Studies have indicated that delivery of climate finance is slow, and disjointed, with developing countries being called on to seek sustainable development which they have no financial infrastructure and international support to achieve. Less adaptation funding is allocated to countries such as Afghanistan which are under acute threat by climatic conditions as compared to their vulnerability. Adaptation and mitigation needs in the country cost an estimated 1.7 billion dollars each year, which is a significant sum of money, but the international climate financing mechanisms have not succeeded in funding the country.

This is a failure that can be partially ascribed to the nature of climate finance. Most funds are taken on a logic of single-project approach which prevents the development of institutional capacity by countries. Projects are a com and go, the ability to design, implement and monitor climate programs however is still weak. Top-down and short-term funding brings about dependency as opposed to empowerment. Societies end up being consumers instead of actors who cannot sustain initiatives once they are no longer provided.

The Climate Literacy Approach to Climate Change.

Being climate literate is having knowledge on how climate impacts society as well as the impact of human activity on climate. A climate-literate individual is able to evaluate scientifically plausible knowledge, discuss climate change in a meaningful way and make informed choices on actions that influence climate. It is more than being aware of environmental justice, it involves the realization of how climate change affects the disadvantaged groups disproportionately, and how to push for protective policies.

The significance of climate literacy is evident on the analysis of policy support. Literature indicates that climate literacy is a better predictor of climate concern and policy support as compared to demographics, life experiences or values. Knowing the processes of climate change, people will be able to appreciate solutions and be involved into decision-making processes. Climate literacy is strongly related to education and media exposure and has little to do with direct climate experience.

Nevertheless, many vulnerable areas do not have climate literacy. In 2022, a PISA test in Kosovo discovered the education system rated among the top 10 lowest in the world, with 50.5% of the population with little or no knowledge regarding the environmental threats to health. The same patterns can be traced in fragile states where the educational systems are not able to incorporate climate science into the curriculum. Even though these systemic issues exist, personal climate literacy can be the driving force of tremendous grassroots activism. One such initiative is the re-establishment of mountain forests in several provinces of Afghanistan by a climate activist, Habibullah Najafizada, in his initiative dubbed (Green Future), in the Daikundi province of Afghanistan. His voluntary community mobilization has seen him planting wild almond, juniper and other native seeds in desolate mountains to fight floods, drought and soil erosion. Najafizada trains the villagers on the ecosystem services, organizes the seed distribution system through the Green Circle centers, and also shows how the restoration of the forest directly contributes to livestock farming and water security. It can be seen in his work; climate literacy is translated into direct action: he attributes scientific knowledge on hydrology and erosion to practical adaptation measures. Instead of being applauded, however, Najafizada has just been arrested by the Taliban intelligence during a three-day period, being punished instead of rewarded in his role as an environmental leader. This paradox shows that there is a major hurdle: although citizens become climate literate and act on their own, authoritarian governance can turn solutions into a security risk instead of becoming a solution, becoming the obstacle to climate action instead of the solution. The outcome is an affected population without the idea tools and political room to deal with its effects in a systematic way.

Capacity Gap in Practice: the experience of Afghanistan.

Afghanistan is an example of an intersection of climate and literacy gaps finance. The nation is exposed to extreme weather threats; droughts, floods, and high temperatures but is not appropriately supported by other nations. With the Taliban takeover, technical capacity has fallen due to mass evacuation of experts and now institutions cannot handle complex climate programs.

Water management has been identified as one of the key priorities in the National Adaptation Programme of Action (NAPA) but there are several limitations in its implementation. The barriers to finances comprise cost of initial technology, subsidy or soft loans, and high costs of building materials. Non-financial obstacles are also quite critical: the lack of good resource management authorities, lack of information regarding the benefits of technologies and poor monitoring systems.

These problems are signs of more profound illiteracy. Absence of technical skill in data collection and reporting in Afghanistan makes it difficult to follow vulnerabilities and to come up with effective adaptation strategies. The institutional and community levels of climate illiteracy imply that even when funds are availed, the institutions will not integrate with the water resource management strategies. Societies are unable to sustain technologies that they are unfamiliar with and government agencies are unable to organize cross-sectoral actions without common conceptual structures.

Policy and Diplomatic Implications

The existing models of climate diplomacy presuppose that the flow of the money of the developed countries to the developing ones will entail the outcomes. This premise leaves out the primary role of climate literacy. Asymmetries in power in international climate negotiations imply that states with a poor technical ability cannot be effective in promoting their interests and raising unfair proposals. They end up being rule takers instead of rule makers and they accept finance packages that need not conform to the local priorities and abilities.

The 2024-2027 programming priorities of the Green Climate Fund focus on empowering the developing countries with improved readiness programs. Yet, preparedness is not just about the institutional processes but rather it entails the development of human capacity to learn about climate science, evaluate the impact of the project and participate in long term planning. The fund is also meant to increase the amount of direct access entities by two folds and enhance early warning systems though none of these can be realized without literate stakeholders who can maintain these systems.

The understanding of climate diplomacy has to realize that literacy is a pre-condition of effective finance. The contracts must have clear capacity building agreements and funding objectives. Action for Climate Empowerment, which is a focus in the Paris Agreement, namely, education, training, and public awareness, requires resources and monitoring mechanisms. Climate finance will otherwise remain a one-way street where only those countries capable of taking it in will receive it bypassing those countries most in need.

Conclusion

The idea of climate finance without climate literacy is really nothing more than paper – documents that pass through international systems but do not change vulnerable communities. As the experience of Afghanistan and other weak states shows, financial transfers are not enough to break the basic capacity gaps. Even well-motivated funding has minimal impacts when the local stakeholders are not knowledgeable enough to design projects, maintain technologies, as well as coordinate across the sectors.

The re-evaluation of a climate policy and diplomacy demands the implementation of climate literacy to the core of climate finance architecture. It implies an investment in long-term education and capacity building, the production of materials in the local languages and the development of the financing systems that solidify, instead of bypassing, local institutions. It involves the realization that the poorest countries in the world do not only need money but also know how to utilize the money.

Climate literacy is not a secondary issue that should be ignored by the international community. On it is based all climate action. In its absence, climate finance turns into a showing of goodwill and not an agent of change. Through it, the vulnerable communities will be empowered as stakeholders in the creation of their own climate-resilient futures. The option is obvious: either keep investing in projects that simply do not work because the country is not that developed, or invest in the human capital that makes climate finance worth the money. The latter is required in climate justice.

Bạn có thể đặt cược tự động theo chiến lược tại 66b mới nhất – tiết kiệm thời gian và duy trì kỷ luật cá cược. TONY01-23

Slot tại 188V có nhiều cấp độ jackpot: Mini (từ 1 triệu), Minor (10 triệu), Major (100 triệu), Grand (1 tỷ+) – phù hợp với mọi mức cược và giấc mơ đổi đời. TONY01-23

Tốc độ tải trang nhanh và không bị chặn là ưu điểm lớn nhất của nhà cái 66b . Bạn có thể truy cập mượt mà trên cả điện thoại và máy tính. TONY02-02O