From Dinner Table Debates to the Supreme Court, Why embedding climate change into constitutional law is the most optimistic move democracies can make

Introduction: The Night the Constitution Saved My Hope

After ten years of engaging in eco-social innovations throughout India, including environmental awareness with communities, renewable energy education, design and prototype development for engineers and rural youth, and leading grassroots climate action, I had reached a point of no return. The result of all projects and all initiatives and even all ardent consultations with the representatives of the government was the same: We will think about it, We’ll make a policy, We’ll see what happens.”

The words became hollow. Policies gathered dust. Promises became PowerPoint slides.

Later on I came across a piece that completely flipped my perspective: In August 2024, the South Korean Constitutional Court ruled that the government had infringed on the people’s constitutional RIGHT to a healthy environment and thus did not protect the coming generations against global warming.

Honestly speaking, I stood up and clapped at midnight.

For the first time, I realized the answer wasn’t just better protests or better data. The answer was the law itself. Not as a suggestion, but as a binding mandate that governments must obey.

This is the story of how democracies can weaponize their own constitutions to save themselves.

The Promise-Policy-Failure Cycle: Why Current Action is Theater

I want to speak frankly with you. I have attended to climate and eco-social innovation conferences, events and workshops, worked with government agencies, civil societies and NGO’s, and researched the methods of climate governance. And this is what I have found out: Climate policies and eco-social innovations that lack constitutional backing are nothing more than recommendations with an expiry date.

When the government changes, policies change. When political pressure fades, enforcement fades. When corporate interests lobby, loopholes expand. I’ve watched it happen in India dozens of times: A national plan is announced with great fanfare (National Clean Air Programme, National Action Plan on Climate Change, Paris Agreement commitments). Targets are set. Timelines are announced. Next year, the priority would have turned around, the money would be different, and the perception of the situation would also be different.

And what about the (NDCs) that nations present to the UNFCCC?

Legally non-binding. The promises at COP meetings? Political gestures. The 2030 targets? Flexible, adjustable, often unmet.

This is not cynicism. This is reality.

On the other hand, as governments are having arguments and taking their time:

• In India alone, air pollution is responsible for 1.7 million deaths every year.

• A rise of 1.1°C in global surface temperature over the pre-industrial era has been recorded

• The extinction of species is accelerating as there has been a 69% decline in the number of wild animals since 1970

• Time is no longer on our side when it comes to flexible targets and non-binding commitments

The Constitutional Revolution: When Law Becomes Law

Now just imagine a different scenario.

What if the issue of climate change was not a matter of “policy” at all but rather a constitutional right that became part of the very foundation of democracy along with the rights to free speech, life and non-discrimination?

This is not a fantasy. It’s a reality.

The Brazilian Constitution (1988) acknowledged and safeguarded the environment in 10 provisions, moreover assigned the judiciary the task of safeguarding environmental rights, which as a result, propelled the slow but extensive development of environmental legislation.

Ecuador (2008) was the first country in the world to recognize the rights of nature (Pachamama) and to grant it constitutional rights, thereby acknowledging that ecosystems possess a value that is not solely defined by human use.

The Kenyan Constitution (2010) recognized the right to a clean and healthy environment followed by a chain of lawsuits that practically compelled the government to tackle environmental issues.

New Zealand (2020) set climate change goals and legally binding frameworks with institutional monitoring.

European Parliament (2021) The UNHRC has come up with a historic resolution that has recognised the human right to a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment, supporting the general understanding of the relationship between the environment and human rights.

However, the South Korean Constitutional Court’s decision in 2024 that the government’s climate policy violated the constitutional rights of society through the neglect of future generations is surely the turn of events with the most far-reaching implications. It was not an indication but rather a command. This was a legal verdict. The government has to act.

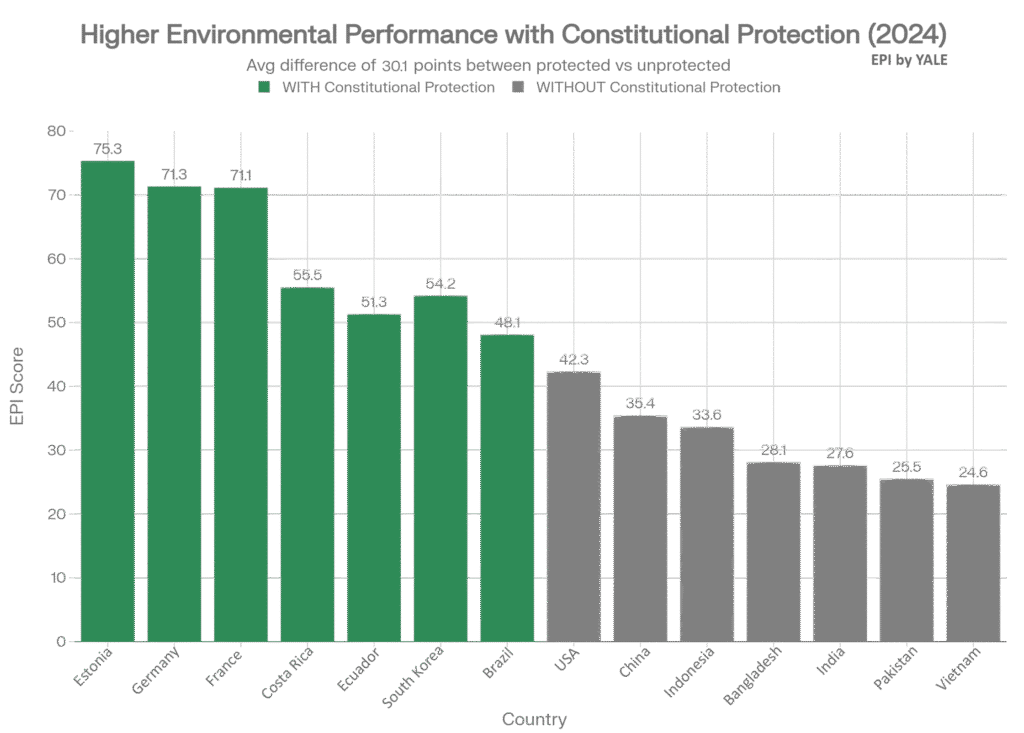

The data is compelling:

Countries where rights of the environment are constitutionally guaranteed tend to be rated 20-30 points higher than the rest who do not have these rights enshrined in their constitutions on Environmental Performance Indices. It is not just a coincidence. It’s causation. Governments provide when it is mandated by the law.

Why Constitutional Protection Actually Works

1. Irreversibility:

The constitutional rights are not easy to modify. You can no longer get up the next morning and say that air quality protection is now not a priority anymore. You would have to alter the constitution an act so politically challenging as to bring accountability.

2. Judicial Enforcement:

Courts become the guardians. Citizens can sue. NGOs can petition. In the event a child is a victim of air pollution leading to asthma, his or her parents can argue that it violates the constitutional provision of life and health. This shift is made between the politicians and the judges who have no electoral reasons to make the environmental protection measures less stringent.

3. The “Standstill Principle”:

When constitutional environmental right is established that is it forever. Belgium, Hungary, and South Africa know this rule: it is possible to enforce environmental protection and never undermine it. This avoids rollbacks in case of changed political winds.

4. Mandatory Implementation:

A constitutional right does not provide an option. It mandates action. The decision by the court of South Korea did not imply that the government ought to take climate action. It stated that the government had broken the constitution because it did not do enough. Policymakers now have to re-write climate plans, according to constitutional guidelines.

The Cost of Inaction: A Comparative Story

Lets me show you the comparison between two countries:

Country A (with constitutional protection):

- Protects environmental rights (constitutional) (established 15 years ago).

- Courts have stepped in on 47 occasions to implement environmental protection.

- Companies make long-term investments, being sure of the environmental regulations.

- The citizens are allowed to file a legal action case in case the air quality surpasses constitutional standards.

- The performance of the environment is gradually increasing.

Country B (without constitutional protection):

- Relies on policies that change with each government

- Environmental enforcement fluctuates dramatically year to year

- Businesses lobby to weaken regulations because they can

- Citizens have limited legal options to challenge pollution

- Environmental performance stagnates or declines

Guess which one has cleaner air?

This isn’t theoretical. Costa Rica had a constitutional environmental protection since 1994 and is currently one of the leading participants in environmental quality and biodiversity protection of the world. India, however, has such a large number of 1.3 billion people and knowledge on the environment and yet they face challenges because the action on climate is dependent on the policies and not on the legislation.

The Failure of current applied Policies.

I should tell the truth about the reason why I left grassroots activism and pursued policy at the. master’s level. It is so because I understood, individual devotion is beautiful, but systemic power is needed in change.

I saw great communal leaders struggle in pursuit of environmental justice with none. institutional backing. I have witnessed great scientists like these giving information to deaf government ears. I observed the actions of NGOs who used lakhs of rupees in awareness campaigns when deforesting there were issued with a signature.

It was not a problem of carelessness. It was non-obligation by law.

You can make a government official move with your passion, but they cannot defy budget. political pressure or constraints. A minister may hold faith in climate action, but when the next one comes, he will. minister does not, it is the opposite. it is possible to have an excellent policy, and the money allocated to enforce it, daggered into other minds, it has no sense.

But a constitutional right? The right guaranteed by the constitution is immortal. It persists across governments, through elections, through political turns and winds.

The Way Forward: Climate Action Constitutionalization.

Therefore, I represent a positive and well-supported case of democracies:

Step 1: Amend the constitutions in order to transform the right to climate change into a. fundamental right.

Not a “duty” but a “right.” The population is entitled to a stable climate and air that is. clean, and a future that is pleasant. This right should be upheld by the government. Ecuador’s situation is a study example: The constitution expressly gives rights to Nature itself. This turns the whole paradigm to Can we save the environment? to “Do we have any legal choice?”

Step 2: Introduce a constitutional climate court or give the current courts more authority.

The example of the Climate Commission in New Zealand is educative. Develop another company that will. monitor compliance with the norms of the constitutional climate and will as well be able to put the government on its toes should the norms be not observed.

Step 3: Relate climate constitutionalism with the rights of the future generations.

The South Korean court decision clearly recognized the rights of the coming generations. A constitutional climate mandate does not mean that we will only think of the target year 2050; we are actually safeguarding the planet for our children. This shift in perspective turns climate action from a mere policy option to a moral obligation.

Step 4: Declare constitutional climate rights as binding (i.e., capable of being enforced in courts).

This is the key. Citizens should be able to sue if the government violates constitutional climate standards, just as they can sue if the government violates freedom of speech. Kenya shows this works.

The Optimism in the Law

I know this sounds abstract. Let me ground it in reality.

At this time, a young activist in South Korea is rejoicing because the constitutional court supported them. A farmer in Kenya is triumphing over a legal battle against environmental destruction because the constitution is on their side. A kid in Costa Rica is inhaling cleaner air as a result of the 30-year-old decision of the country to make environmental protection part of the supreme law. This is not the stuff of dreams. This is happening.

As one of my professors always quotes

“the best time to plant a tree is 20 years back”

And it’s the most hopeful thing I’ve discovered in my decade of climate work. Because it means the fight isn’t hopeless. It means we have a tool “a legal tool” that transcends politics, personalities, and power shifts.

The constitution is written to last. It’s written to protect future generations. And if we embed climate action into it, we’re essentially telling the future: “You are protected by law, not just by promises.”

Conclusion: From Dinner Table to Courtroom

When I was younger, I thought climate action required everyone to change their minds. I organized seminars. I created awareness campaigns. I had conversations with policymakers, hoping they would see the light.

I was naive. I was relying on hope instead of leverage.

Now I understand: The most powerful climate action is the kind that doesn’t depend on hope it depends on law.

When climate protection is constitutional, it’s non-negotiable. When it’s embedded in the supreme law of the land, it becomes as foundational as democracy itself. When citizens can sue to protect it, it becomes powerful.

This is not to diminish the work of grassroots organisers, scientists and. Their work is sacred. But it needs to be backed by law. The Constitution is the ultimate commitment device a way for a democracy to promise not just to its present citizens, but to its future.

As someone who has spent over a decade in this space, moving from community organizing to policy study, I can tell you: I’ve never been more optimistic. As I observe it, this is the very first time when I perceive a mechanism that is capable of surviving through bad leadership, political indifference, and short-term thinking. The Constitution can be our saviour, but with the condition that we make amendments in such a way as to secure the planet’s future. The courts are waiting. The laws are being written. The precedents are being set.

The question for democratic societies is no longer, Should we take action on climate change? The question has now changed: Are you willing to help it with your dollars and turn it into a constitutional issue?

Heya this is somewhat of off topic but I was wondering if blogs use WYSIWYG editors or if you have to manually code with HTML. I’m starting a blog soon but have no coding expertise so I wanted to get guidance from someone with experience. Any help would be greatly appreciated!